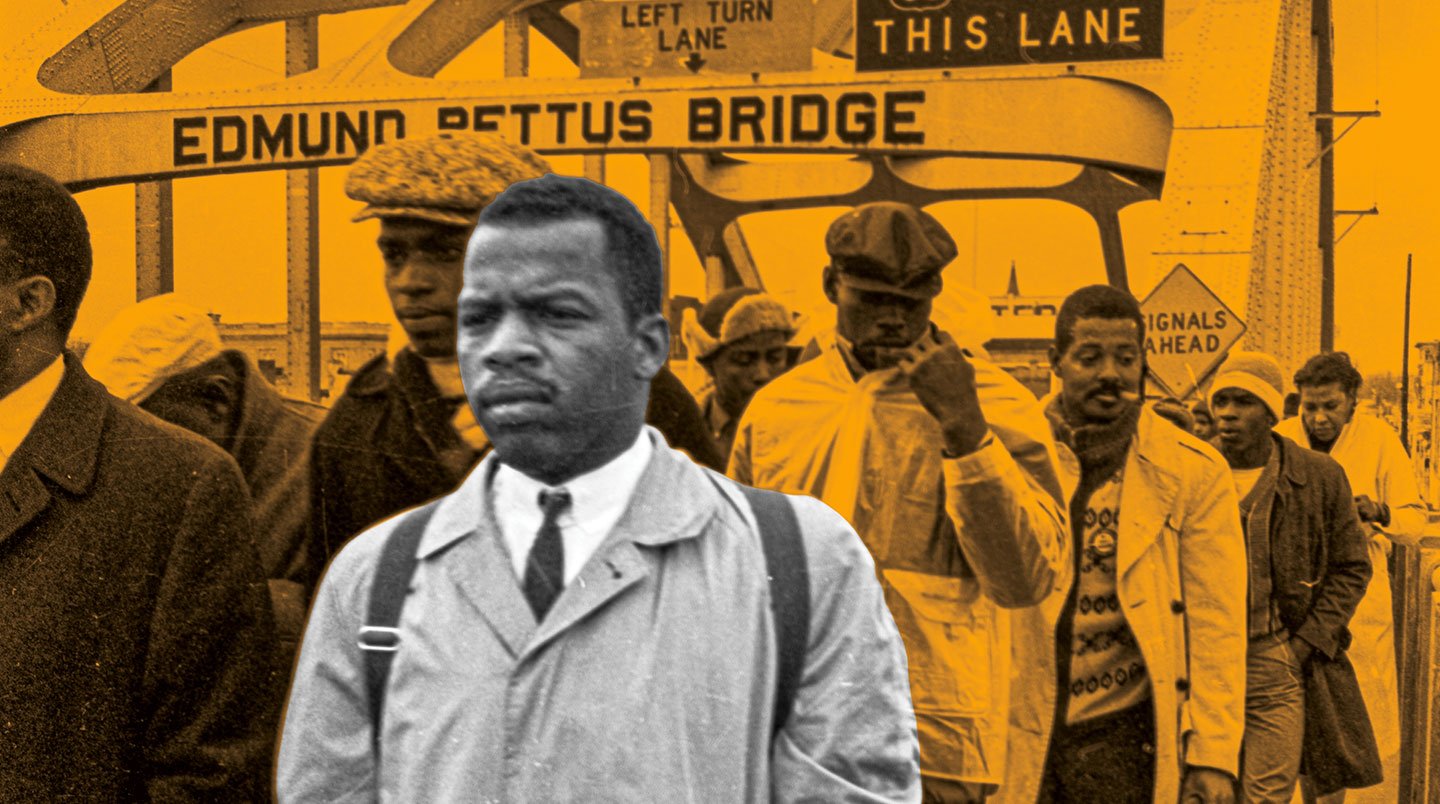

AP Images

Attacked

Lewis—and about 60 other peaceful protesters—were injured by state troopers on Bloody Sunday

It was 3 p.m. on Sunday, March 7, 1965. Twenty-five-year-old John Lewis led the way onto the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. Behind him were 600 protesters, walking peacefully two by two. Their goal was to march 50 miles to the state capital of Montgomery. There they would demand one of the most basic of freedoms: the right to vote.

Halfway across the bridge, Lewis stopped in his tracks and stared ahead. He saw a wall of blue—dozens of Alabama state troopers in uniform. Behind the troopers were more men in regular clothes. They carried clubs the size of baseball bats.

Lewis wasn’t sure what was about to happen. But he knew it could put lives at risk.

He also knew it could change the course of history.

It was Sunday, March 7, 1965. John Lewis was 25. He stepped onto the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. Behind him were 600 others. They planned to march 50 miles to Montgomery, the state capital. There they would demand the right to vote.

Halfway across the bridge, Lewis stopped. Ahead of him were dozens of Alabama state troopers. Behind them were more men. They carried clubs the size of baseball bats.

Lewis wasn’t sure what would happen next. But he knew it could put lives at risk.

He also knew it could change the course of history.

At 3 p.m. on Sunday, March 7, 1965, 25-year-old John Lewis led the way onto the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. Behind him were 600 protesters, walking peacefully two by two. Their goal was to march 50 miles to the state capital of Montgomery, where they would demand one of the most basic of freedoms: the right to vote.

Halfway across the bridge, Lewis stopped in his tracks and stared ahead. He was facing a wall of blue—dozens of Alabama state troopers in uniform. Behind the troopers were more men in regular clothing, carrying clubs the size of baseball bats.

Lewis wasn’t sure what was about to happen, but he knew it could put lives at risk.

He also knew it could change the course of history.